You can't always get what you want

But if you try sometimes

You might find you get what you need

—The Rolling Stones

A big worry that diabetics who want to travel somewhere often have is how to travel safely with diabetes supplies. Carrying insulin so that it stays cool and safe, and needles so security personnel don’t give you too hard a time, and keeping enough of what you need and guarding against damage or loss – it can be overwhelming.

Diabetes and other travel gear in a hotel room in Estonia.

But, as with most things in life, the worry is far worse than the actual reality once you get there. Just take a few precautions and you can stop fretting. Even if a problem arises, you’ll figure it out even if you don’t know how right now. (And if you knew everything that was going to happen beforehand, there’d be no need to travel anyway, right?)

I’ve traveled to many countries, usually on extended months-long trips, with Type 1 diabetes. I’ve been to hot places, to cold places, to areas where my types of insulin and blood sugar testing strips are readily available, other areas where they weren’t, and everywhere in between.

Trekking around China, insulin in the backpack.

While I’ve had no emergencies when it comes to diabetes supplies (I question whether such a thing really exists) I have had a lot of experiences with traveling with ‘betes gear. Here are some of the situations I’ve found myself in, and some of the things that may happen to you when you’re traveling the world with diabetes. I hope you find some inspiration and some reasons to relax in these stories from the road. Remember always – you can go anywhere with diabetes!

Humalog shot in Dubrovnik, Croatia.

Bloody water on the Norwegian border

I was on a train from Sweden into Norway one October afternoon. At the time, I was using a steel Humalog insulin pen with little replacement refill canisters. When I was done with one, I’d put it in an empty plastic water bottle I carried in an outer pocket on my backpack. I put my used BG strips in the bottle too, and any other weird-looking diabetes cast-offs one accumulates.

Hey, I was being clean and environmentally friendly, in my way.

On a Norwegian train.

I’d been carrying the bottle for a couple of weeks when the train crossed the Norwegian border on its way to Oslo, and the bloody strips had turned some remaining water a muddy reddish brown. In this sick looking slush were bits of paper, white plastic strips with dried blood on them, unscrewed needles, and spent glass insulin refills.

It was unsightly, perhaps, but was concealed in a pocket of the bag and not displayed publicly.

The procedure when crossing the border was that a woman came on and walked the aisles, checking passports and credentials. And, sometimes, people’s luggage.

When she got to me, she ok’d my passport and my Scanrail train pass, then asked to see what was in my backpack. With an offhand and humorless efficiency she unzipped and poked around, finally getting to the pocket with the bottled mutant lab experiment in it. I wondered what she’d think. I hoped I wasn’t in violation of… something.

She found it and held it up to get a good look at it, high where the sunlight coming in the train windows could illuminate the mysterious-looking thing. In English I explained briefly that I was diabetic, but braced myself for the reply.

But there was none. She put the bottle with its bloody water and needles back in its pocket, satisfied, and moved on to the next seat. And that was it. My worry had been for nothing, not for the first time.

I learned to relax a little, and I also learned that claiming medical necessity could smooth over potentially sticky situations. Security people aren’t interested in your health, but certainly don’t want to be responsible for a medical problem.

Suspicious Vietnamese border guards

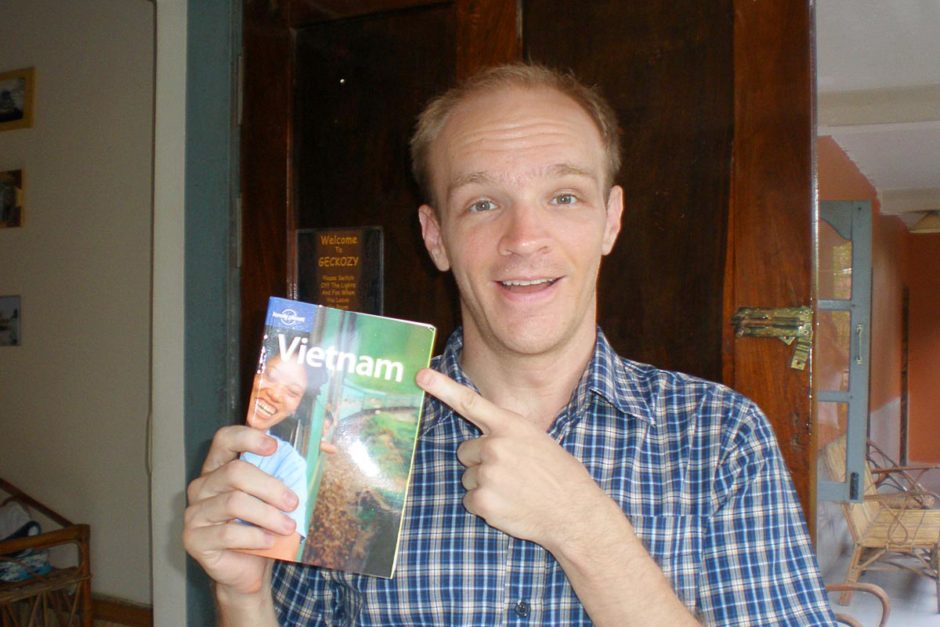

Entering Vietnam from Cambodia at an obscure crossing in the far south, I managed to raise the suspicions of some Vietnamese border guards who were rifling through my backpack.

Trying to enter Vietnam with a bag full of insulin pens.

The crossing had been open for years but had only recently opened to non-locals – and the Kampot (Cambodia) to Hà Tiên (Vietnam) checkpoint was a little-used one, in the middle of nowhere and accessible only by hired transportation. My travel partner Masayo and I were wearing motorbike helmets as we stood in the hot Mekong sun hoping to get our passports stamped.

But I had a foil bag full of insulin pens, as well as several pen needles in a bag and, as backup, 50cc syringes. The guards had clearly not seen anything like this before and didn’t know what to make of it all.

They weren’t aggressive or hateful about it, but it was clear that they regarded this as a potential big problem. It was up to me to explain myself and be allowed into their country.

So I did all I could: they spoke no English and I spoke no Vietnamese, so I resorted to gestures. How do you mime “diabetes”, extemporaneously and for an audience likely unfamiliar with the condition? I tried – injecting, checking my finger, eating. Between each part, I’d look at them with a bright, encouraging face, as if to say, “See what I mean? You know, diabetes!”

It wasn’t working. The guards were getting more confused by the minute.

As a last resort, I realized there was an outside chance that “I am diabetic” might be in the bootleg Lonely Planet Vietnam guidebook we’d bought in Cambodia. (Some Lonely Planets contain the phrase, though most don’t.)

The guards eyed me expectantly but dubiously as I flipped through the book to the phrases section. And there, in poorly-printed ink, was the smudged Vietnamese word for “diabetes”.

I showed the book to the guys, pointing excitedly. Instantly, they broke out into smiles, relieved that all was well and that they understood. They reassuringly told me I could bundle up my weird-looking supplies and proceed through the gate. I thanked them and Masayo and I got our passport stamps and continued the adventure.

I learned from this that, as in Norway, as long as people understand that things are for diabetes, everything is fine. Lonely Planet saved me this time, but in the internet age carrying guidebooks is increasingly outdated. It’s good to at least have a piece of paper with you that has the local word for diabetes printed on it so you can communicate that.

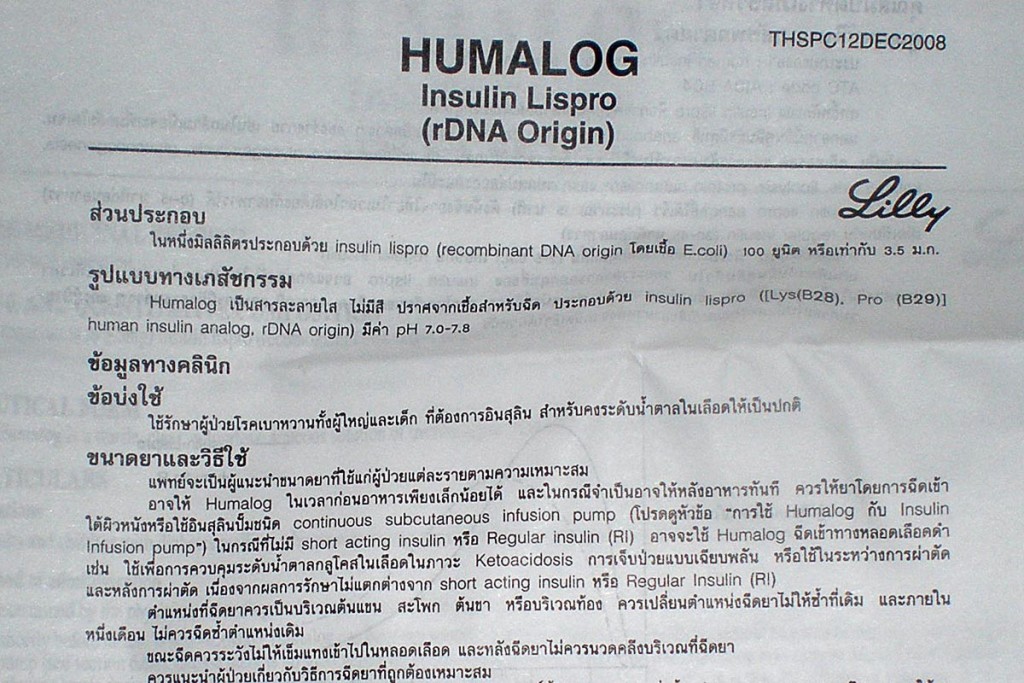

Humalog insert in Thai.

Explaining things to the TSA in America

The United States’ Transportation Safety Administration is infamous the world over, for all the wrong reasons. I’ve talked to many people who travel, and they always shake their head and sigh when America comes up in conversation.

As an American citizen I have often passed through the security screening in American airports and have never had any truly difficult situations. I have had to explain what an insulin pen was a couple of times, uncapping it and showing them the needle. They often don’t seem to really understand, but give me the benefit of the doubt. Even having dozens of pen in a foil pack with a big ice pack has never roused any suspicion (in the US or elsewhere).

Maybe I have a kind face.

Terrorism juice in Hawaii

On a trip to Hawaii I changed planes in Honolulu. It involved leaving one airport and walking up some stairs along a short road to another local airport.

At the second one, the security guy objected to my bottle of orange juice, which I’d purchased ten minutes earlier in the arriving airport. Having spent the last several hours crammed into an Economy class airplane seat I wasn’t really in the mood for the TSA’s brainlessness, but I knew that arguing is futile.

But I couldn’t help it. I stressed that I’d just bought it inside the airport, and explained that it was for low blood sugar. And still sealed. Et cetera. (I refrained from wondering aloud how I might blow up an airplane with a bottle of Minute Maid; I’m sure they hear that multiple times a day anyway.)

Hawaii.

He patiently explained that, since this airport transfer involved a short stroll outside, that it was theoretically possible that I acquired the juice then, and it hadn’t in fact come from an airport shop. Irritable but resigned, I fumed silently at this.

But he determinedly eased my worry – by saying that since I’d explained to him that it was a medical situation he was going to let me through with the juice. I was pleasantly surprised; I thanked him and continued on.

The impression I got was that he thought the rule was as stupid as I did, but couldn’t overtly say so. So he was communicating it to me in so many words. And, most importantly, letting me take the juice. If we travelers are going to have any satisfaction in the future with the TSA, I think the staff themselves being annoyed by the meaningless regulations will be part of it.

Buying new supplies while traveling

Aside from carrying things around, you will sometimes need to buy diabetes stuff in other countries. Regulations about insurance and prescriptions vary, as does the availability of certain products.

As usual, you will be fine anywhere you go, since medical professionals want to help and will have something for you, even if it’s not exactly what you’re used to.

Here are some of the many experiences I’ve had getting supplies on the road.

At a pharmacy in Serbia.

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

I went into a pharmacy in the capital of Malaysia one day and they found someone who spoke English. I showed him my insulin pens and he looked it up – and said he could order it. I told him how many I wanted (there was a limit, he said) and made an appointment to come back in a couple days. I did, and they were ready. No prescription needed, and no fuss. The price was about the same as the United States.

Chumphon, Thailand

At the local public hospital in the small southern town of Chumphon in Thailand, as a bird flew lazily around the cavernous waiting room, I was told by a doctor with surprisingly good English that while they couldn’t get Humalog, they could get ActRapid. Having little choice, I asked her for a prescription and came back in a couple days to pick it up. I bought several vials, plus syringes (they didn’t have pens). I was able to get as much as I wanted, and it was really cheap. And it was effective; I used it for many weeks without problem.

Supplies from the hospital in Chumphon, Thailand.

Vientiane, Laos

Vientiane may be the capital of Laos, but when I was there I couldn’t find any diabetes supplies anywhere. Laos was just too run-down. But the town was on the Thai border, and I contacted a hospital in the town of Nong Khai on the Thailand side by email. In English, they said they could get supplies to me, and told me the prices for everything I needed. They’d deliver it to me by motorbike; I might have to pay a small premium but the service seemed great. Even in a country where medical facilities were sparse and unreliable, I found a way.

Seeking insulin at a hospital in Vientiane, Laos.

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

At a pharmacy in Cambodia’s capital, I asked about ActRapid or Humalog. They had ActRapid – at a cooler in the middle of the store, very cold, was a box of five pens. (No vials! I was excited.) I said I’d take them, but then noticed that the expiration date, which was that very day. He got a secretive look on his face and enquired if I might like to buy them for half price. “Sure!” I said. I did, and they too turned out to be fine.

Huế, Vietnam

As in Chumphon, Thailand, in Huế I had to go to a local hospital. They scrounged up an English-speaking doctor, who interviewed me briefly about my diabetes history. Then he wrote a prescription, and I was led to the hospital’s pharmacy where I bought what I needed. Again, cheap, helpful and no problems.

On the way to the pharmacy in Huế, Vietnam.

Hohhot, China

My only experience buying supplies in China was in Hohhot in Inner Mongolia, northern China. In a pharmacy full of large bottles of strange-looking “traditional medicine” (leaves and various animals floating in colored liquids, it looked like to me) I ordered Humalog, Lantus, and OneTouch Ultra test strips. They let me order as much as I wanted, told me to come back in a couple days, and had everything I asked for. The price was fine – average – and there was, as usual, no problem with any of it.

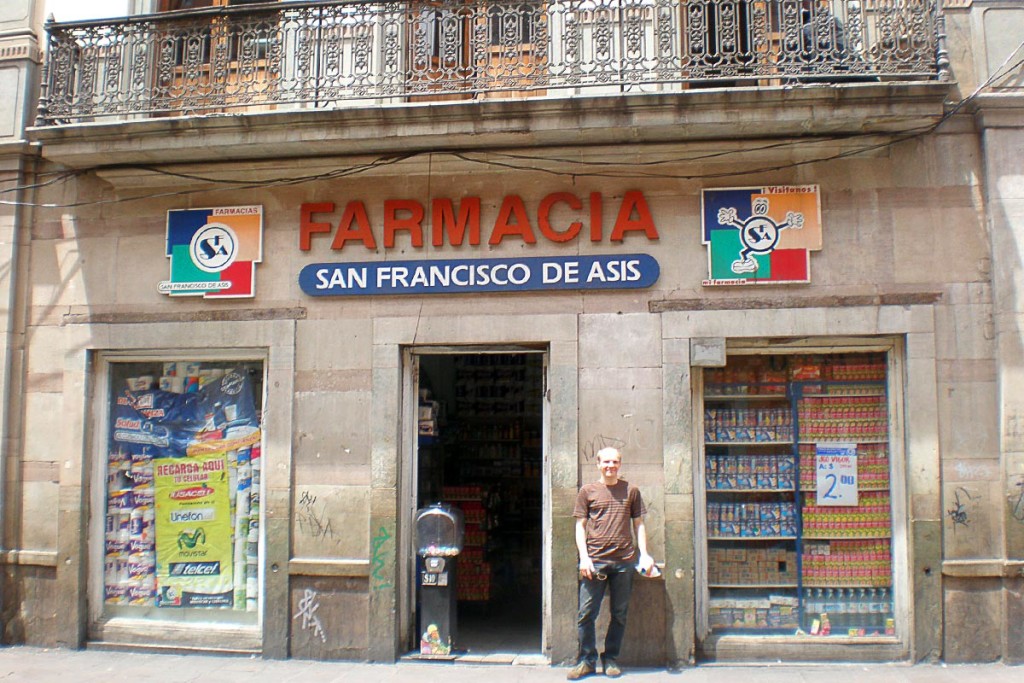

Guanajuato, Mexico

At a pharmacy in this lovely mountain town I asked if they had Humalog. The pharmacist shook her head apologetically but firmly. Nope. I tried another couple pharmacies and got the same reaction. At the final place they again said no but suggested I try a certain pharmacy – the first one I’d been to. Having no alternative ideas I did in fact return, and of course the answer was still no. But then I asked if they could get it, and they said yes.

I learned from this that there can be a difference between “Do you have X?” and “Can you get X?” Always be clear!

Bodø, Norway

I needed Lantus, and a pharmacy in Trondheim told me I needed a prescription. I didn’t want to pay for a doctor visit so I held off until arriving in Bodø, further up the chilly February coast. At a pharmacy there I explained my situation and the lady said the same thing. She was actually from Stockholm, Sweden, and had moved to Norway just for fun. Seeing my disappointment when I explained that I was just passing through and had no doctor to visit, she said she could invoke an “emergency” contingency that would allow her to sell it to me for an extra fee. I agreed, and walked out with my Lantus pens. Not cheap, but not too far above what I would have paid anyway.

Norwegian pharmacy.

There’s always a way to get supplies

I have yet to find a place where I absolutely couldn’t get what I needed. It takes some patience, some flexibility, and perhaps some persuasion, but something will always work out. It’s usually best to stock up on stuff when you can – it is possible that you won’t be able to get what you need somewhere – but you won’t run out of stuff and drop dead on the spot.

May all of your BG checks in Slovenia be 106.

Diabetes doesn’t add problems to travel, it promotes ingenuity and perseverance. You’ll find a way, and people will help you if you’re friendly and patient. Relax, and enjoy your travels – don’t let diabetes stop you from doing anything.

Thanks for reading. Suggested:

- Share:

- Read next: Review: Gear4U Camping Cookware After a 3-Month Trip

- News: Newsletter (posted for free on Patreon every week)

- Support: Patreon (watch extended, ad-free videos and get other perks)

Support independent travel content

You can support my work via Patreon. Get early links to new videos, shout-outs in my videos, and other perks for as little as $1/month.

Your support helps me make more videos and bring you travels from interesting and lesser-known places. Join us! See details, perks, and support tiers at patreon.com/t1dwanderer. Thanks!

Excellent post! I am always curious about getting supplies in other countries. I always just pack enough supplies as if I were moving there and tell security and immigrations that me and all my travel companions have T1D ha! Love your message that nothing bad will happen. Too often I hear of Type 1s letting insulin and supplies be their excuse for not traveling

Thanks Zach! Yeah many T1Ds do fear traveling so much that they convince themselves it’s not worth it. But actually it’s no problem.

One thing though, I wouldn’t personally lie about my travel companions having T1D as a way to get by security with lots of insulin. Seems like an unnecessary can of worms to open.

Is it possible to get an ‘extra’ baggage allowance in the cabin to carry 5 months worth of supplies? What are the airlines attitudes to this?

Maggie,

I’ve never tried that. I would imagine there is certainly a way. I don’t know if it’d be free though. Is five months’ worth of stuff too big and/or heavy?

Since medicine can be delicate and you wouldn’t want to put it in checked baggage, I’m sure airlines have a way to accommodate you and probably deal with this often. You’d have to contact an individual airline to see what they say. And of course the actual situation in the airport is often different. (Good or bad – often they don’t really enforce the limits that much, especially if it’s medical related. They just want to herd everyone on the plane.)