I'll find somewhere

Where they don't care

Who I am

—Neil Young

Does the time you spend in a place always match the general atmosphere of that place?

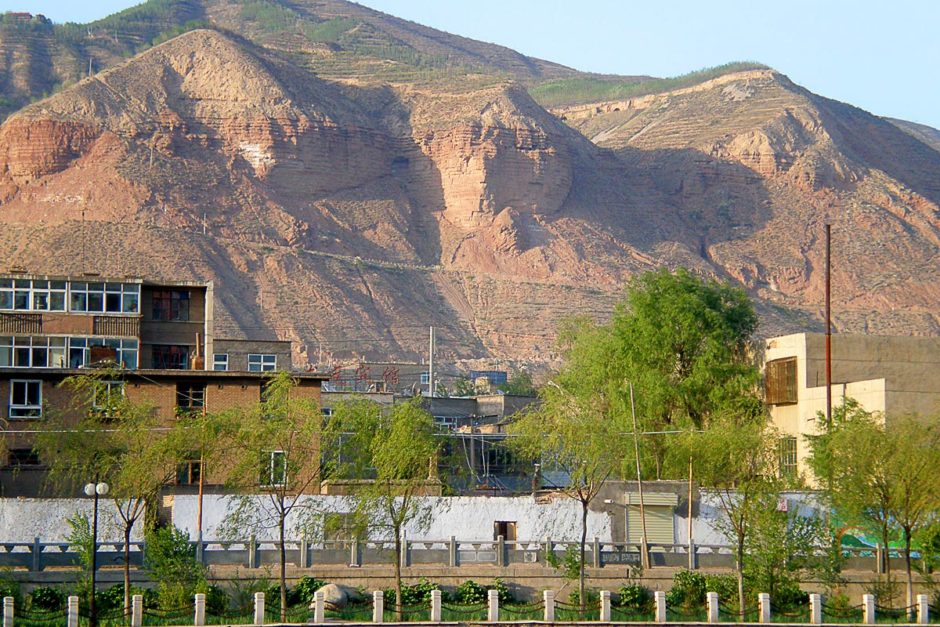

When Masayo and I spent three days in Xining (西宁), China, it certainly did. Xining (pronounced “shee ning”) is a city in vast Qinghai Province in western China. It’s a high, arid, chilly place, hidden behind huge red rock bulges in the earth with an opaquely muddy brown river storming through it.

Utah, eat your heart out.

And our time in Xining took on that spirit: we didn’t do too much or see too much, we just spent three days in slow motion, contemplating the high sun-shadowed rocks visible from town, passing time in large and mostly empty coffee rooms, and walking along the river like the only two people in a place left behind when humanity escaped to colonize another planet.

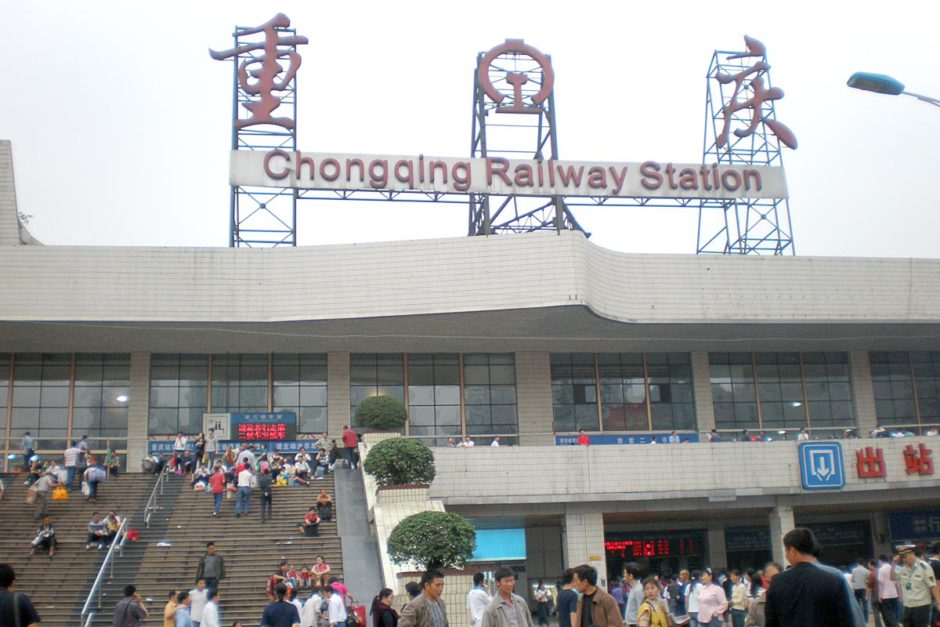

Leaving Chongqing station on a grey smoggy day.

Well that may be a bit of an over-dramatization; Xining is in fact the largest city on the huge Tibetan Plateau, the capital of Qinghai, and thanks to the train line that reaches far into this remote part of China, a transportation hub. It has some nice things to visit – mosques, temples, and parks, and other remnants of Xining’s past as an important stop on the Silk Road – but it’s just as easy to relax here, to feel like you are visiting a place that no other traveler has ever heard of.

Me in Chongqing station – insulin and strips in each bag.

And after our very lively past couple of weeks, that was what we needed. After our three-day Yangtze River boat tour we had spent a couple days relaxing in Chongqing, but we were in the heart of that gigantic and dingy city; Xining, by contrast, felt soothing and calm. Distant, but welcoming.

Wild and arresting scenery on the way to Xining.

It was a 21-hour overnight train ride from Chongqing that got us to Xining. Masayo and I each had a top bunk in the third-class sleeper car, where we were comically cramped but restful enough. As the train made its steady way through the high-altitude, dusty plateau, I was thrilled to find that there was a gadget on the wall of my bunk written in three languages – Chinese, English (“oxygen supply” it read) and Tibetan.

This fascinated me more than you would think.

Tibetan! There is nothing like a new language and a new script to dramatically demonstrate that you are heading for new frontiers. We weren’t actually headed to Tibet (too much expensive paperwork involved; Tibet deserves a trip all of its own, not as a side trip from China) but the train was. Imagine! We were so far out of anywhere we knew that things were written in Tibetan! I loved it.

The villages we passed looked like this – tiny, muddy, and cramped. All I have is this blurry photo taken from the train, but I wonder what it’s like to visit one of these places…?

Diabetes report – Overnight train food

Chinese trains often have a dining car, and I checked it out on this trip to Xining. Food is nothing fancy – meat and vegetables in a sauce, served with white rice. You can also get noodles and of course big, cheap, not-particularly-delicious bottles of Chinese beer.

When not eating in the dining car, meals tend to come from a shop. Every big station platform has some people selling simple snacks and instant foods; I’d hop out and buy some instant noodles or even some cookies for low blood sugars.

Masayo enjoying the dining car between Chongqing and Xining.

The biggest diabetes issue with overnight trains in China isn’t the food supply, or the quality of the food itself, but the lack of activity and the physical stress of the sleeping arrangements. Mostly people are quiet at night, but noises and the motion of the train can jar you awake. That might not hurt your blood sugar, but it won’t help.

So you’re unlikely to wake up refreshed the next morning. Happy maybe, but not full of zesty life necessarily. And there isn’t much to do during daylight hours except sit by the window and watch China roll by. Fun, but again not conducive to great blood sugars.

It is possible to sneak in some exercise: if you have a second- or third-tier bunk assigned to you, you can climb up and down it as long as you aren’t annoying others. And you can walk up and down the train, though there are often so many people in the aisles that it’s not much of a cardiovascular workout. But at least you’re moving around.

Of course you can avoid long-distance trains by just choosing destinations closer to you, but in a land the size of China that usually means on a regular tourist visa that you wouldn’t have time to visit the more far-flung places. Which would be a shame – everywhere in China is unique and no place should be missed if you can help it.

So do your best with blood sugar – use your diabetic ingenuity to make sure your body doesn’t atrophy too much, try to mix in some decent foods with whatever simple things you’re finding to eat, and check BG often.

And feel glad that you’re in such an amazing place having such a huge adventure. What else is life for, after all?

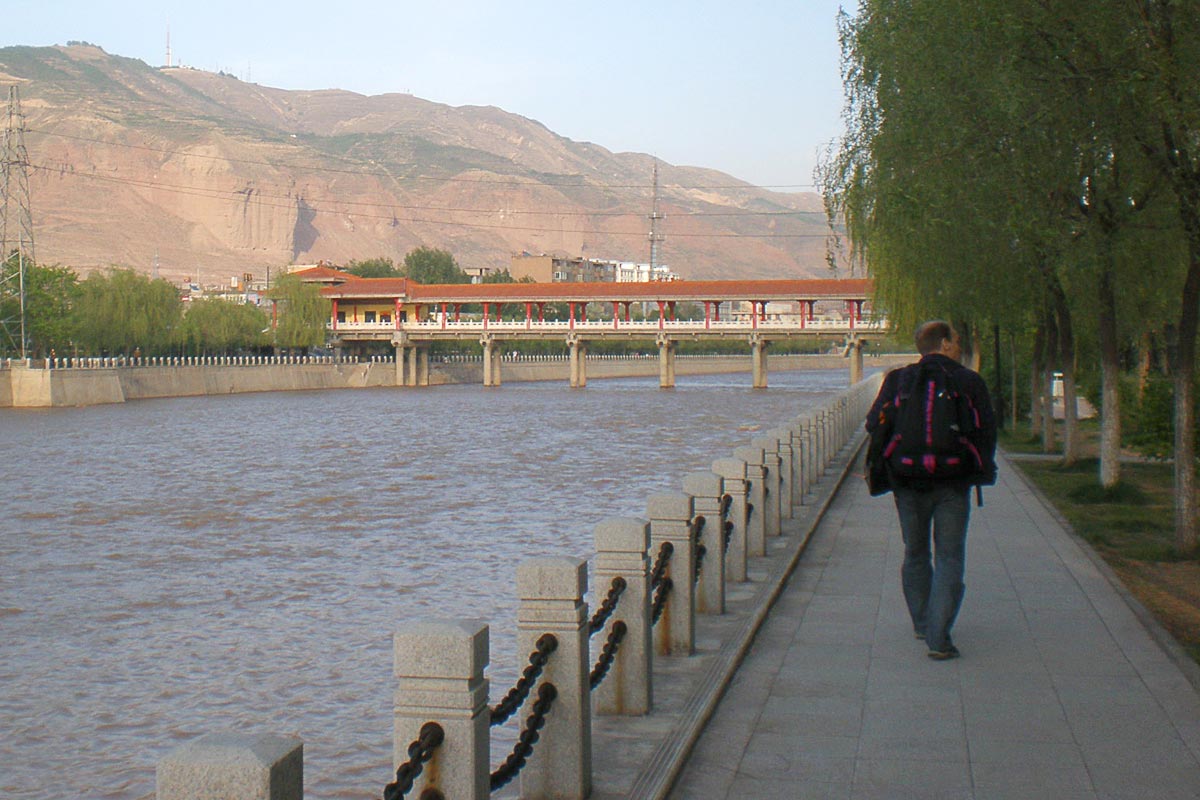

Around 5:00 pm the next day we rolled into Xining, where everything is brown. The street in front of the station was a wide muddy path beside the bright tan Huangshui River (湟水河), which flowed rapidly with choppy waves between long, straight concreted walls. The brownish-red cliffs rose behind the train station area and extended far into the distance on either side; the late afternoon sun brought out orange-reds of the prominent parts and turned the recesses into blurry shadows. Breaking up the color scheme were bursts of green trees.

Xining is earth tones writ large.

Xining train station, the next day.

Crossing the river on one of the bridges we found ourselves in a nearby hotel. The rates were listed on the wall, as they usually are in China, and were acceptable to us. But the woman working there spoke no English at all, and seemed uncomfortable completing the transaction without it: she wanted to get it right. (She spoke to Masayo, thinking she was Chinese, but Masayo smiled in her practiced apologetic “actually I’m Japanese” way, and the surprised clerk gave up.)

So she made a phone call and in a couple minutes an older man showed up who spoke some English. He guided us through the check-in process and we had our room. Thankful smiles all around!

That night, as it rained, we walked around the busier part of Xining which was situated rather high above the river banks. We ended up at a food stall run by guys who looked Central Asian cooking up bread and lamb skewers. One of the guys had visited Japan and, in halting English, we discussed the land whence we ourselves had come. The food was excellent.

Otherwise we just existed in Xining for a couple of days. We walked around the town’s steep and then flat streets, looking at the buildings, feeling the isolation of its setting, and listening to the cheerful birds and the river, always hissing a few blocks away.

Huangshui River in Xining.

After recharging ourselves, and consulting various maps of China (both online and in our Lonely Planet guidebook) we made vague but exciting plans to go even further into the wilds of western China – maybe through the Taklamakan Desert, and/or to Kashgar or Ürümqi or Turpan. Our visas may be running out but we still have time to do some exploring.

So it was that we spent a few days in this ancient crossroads of a town, full of influences from a wide range of cultures and with its own style quite separate from the rest of China. And we used it as a way of psychologically adjusting to being in what is really a separate country – western China. This is clearly not the big cities of the east (Shanghai, Beijing, et al). This is like the dusty edge of the world, where only the hardiest go.

Research on the last day in Xining: we found a cafe with wifi.

But there is (as always) much to be seen. We haven’t even seen the Great Wall yet!

What’s the most interesting place you’ve spent resting and recuperating during a long trip?

Thanks for reading. Suggested:

- Share:

- Read next: Day 74: Golmud, dusty crossroads on the edge of nothing

- News: Newsletter (posted for free on Patreon every week)

- Support: Patreon (watch extended, ad-free videos and get other perks)

Support independent travel content

You can support my work via Patreon. Get early links to new videos, shout-outs in my videos, and other perks for as little as $1/month.

Your support helps me make more videos and bring you travels from interesting and lesser-known places. Join us! See details, perks, and support tiers at patreon.com/t1dwanderer. Thanks!

Greetings,

I stumbled onto your blog and appreciate the report, especially the trip between Golmud and Dunhuang.

It reminded me of a trip I did in 1994/1995, traveling along the Silk Road from Xian to Kashgar. As a sidetrip, I did take a bus from Dunhuang to Lhasa (and back in order to continue my journey out to Kashgar and then onto Pakistan). That bus journey took then 39hours each leg…

Absolutely wonderful memories.