The scream of the ambulance is sounding in my ear

Tell me Sister Morphine, how long have I been lying here?

What am I doing in this place?

And why does the doctor have no face?

—The Rolling Stones

The trip took an unexpected veer off course in the last week: wracked with a mysterious sickness I had to flee Vientiane, Laos and be dragged by ambulance back across the border to a hospital in Thailand. I’m getting better now, but it looks like the Laos part of this long Southeast Asian trip is suddenly and unexpectedly over: Masayo and I have decided to stay in Thailand while I recuperate.

This whole story dramatically highlights the difference in health care in Thailand and in Laos. And it seemed to have nothing to do with diabetes, although it certainly didn’t do my blood sugars any favors. On the plus side, Masayo proved to be a source of unbelievable support. Without her I shudder to think what might have happened to me.

The last few days in Vientiane

As we had been doing since crossing the border last week, we’d been enjoying small-town Vientiane, a cute and manageable world capital if there ever was one. No big buildings or bustle, just small shops and restaurants and lazy walks by the big, slow, muddy Mekong River with the wind blowing hot air through the green trees above.

One day we ate at a typical riverside restaurant; I had a place of fried rice. On an elevated wooden deck we ate our food and looked out across the Mekong towards the town of Nong Khai, Thailand, which we’d stopped briefly on the way from Bangkok into Laos. It was a nice day, marred only by the metal staple I found in my rice. I’m lucky I noticed it in my bite of rice and didn’t swallow it.

Should I worry about this? Well, as it turns out… maybe.

But soon afterwards I began to feel bad. It started one morning when I awoke with a small fever. Unusual for me. It wasn’t bad, but it made me curious about what my medical options would be in Laos so we set out to get some information.

First, the International Clinic at Mahosot Hospital in the center of Vientiane was closed for lunch so we went to the American Embassy; they too were at lunch. Back at Mahosot they were back but thanks to language difficulties I was getting nowhere. I realized that if I had a problem, this place would be useless for me.

The Embassy was still closed so we had lunch nearby while we waited. Finally I was able to speak to a guy at the Embassy, who told me a few basic points that were indeed helpful:

- Due to poor health facilities in Laos, the Laotians have an agreement with Thailand to send patients across the border if necessary.

- He couldn’t vouch for this since it didn’t involve the U.S. directly.

- Neither could he vouch for or offer any opinion about the thyroid pills I’d bought at a ramshackle stall a couple of days ago and had been taking.

As it turned out, I’d get this information just in time. That night things got bad.

Sickness sets in – all the colors of the rainbow

That night I felt so bad that I couldn’t go out for dinner as planned with Masayo and a Japanese tourist we’d met in the lobby of MOIC Guesthouse. (This wasn’t Akiko, with whom we’d had dinner the other night; this was yet another Japanese visitor.) They went out while I laid in bed.

Eventually I was vomiting, a lot, until my stomach was totally empty. But still I kept vomiting, each time a different and more frightening color. Green, then yellow, then brown, then black… I’d never had anything like it in my life.

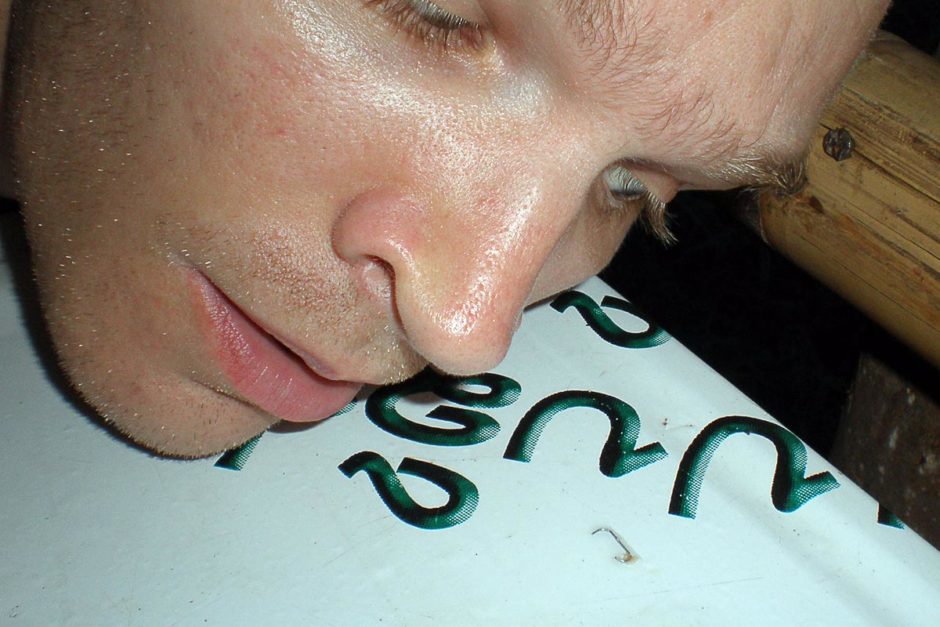

Me posing with a bag of raisins and cashews – that I would be unable to eat.

You know how when you’re sick and you throw up, you feel better for at least a little bit? Well after a while, even those little windows of calm went away. They got shorter and shorter until I was throwing up and still feeling rotten.

Throughout all this, I’d occasionally force myself to check my blood sugar which was always high. I was taking ActRapid insulin to get it down, and still taking my Lantus at midnight, but it wouldn’t come down. Anyway, diabetes took a back seat to the mysterious illness at hand. I had no problem living with a 300+ BG until I got better.

I think this blurry, fevered photo captures the situation perfectly. Note uneaten pumpkin soup and strawberry milk.

This went on for a couple of days; Masayo would bring me food but I couldn’t eat it. Pumpkin soup from Joma Bakery Café would have been perfect but I could keep nothing down. I’d have a tiny slurp and instantly be in the bathroom vomiting. A single drop of water? Same thing.

Looking for the American Embassy in Vientiane. It’s the white building on the right.

Masayo urged me to go to the hospital in Thailand but I refused. I don’t know why, now; maybe I didn’t want to pay for hospitalization. (I have no insurance.) But finally it had gone on long enough, and I was weak enough, that we had to do something about it. What followed was one of the most difficult days either Masayo or I had ever had.

International ambulance day

Note

I’ve made this story pretty detailed to give you a sense of what we had to go through. Nothing seemed to go right for us. All part of the adventure of traveling – in retrospect, anyway!

On the third day of the sickness, at 5:00 am, I told Masayo I needed to go to the Thai hospital and get an IV to be rehydrated.

In the confusion of our conversation, Masayo misunderstood and thought I wanted her to call the Mahosot Hospital a few blocks away in Vientiane. She did so from the guesthouse desk and was told that they’d open at 8:00 am and, while they had no ambulance, we could take a tuk-tuk then.

Useless. I needed more, and fast. I told Masayo no, call the Thai hospital.

The front desk at our guesthouse claimed to be unable to make international calls so Masayo stepped out into the early dawn light to a nearby internet cafe. They were closed, but Masayo banged on the door until a cleaning guy opened it. She explained, with difficulty, that she needed to use the phone and made the call, using a phone number from our Lonely Planet to Wattana Hospital back in Nong Khai, Thailand.

She spoke to a guy there, in English, who seemed extremely confused about the need for an ambulance to come across the border. He kept confirming it, over and over and over.

He said he needed the phone number of the hotel so she had to hang up and go get the number from the front desk. Back at the closed internet cafe, there was now a woman inside who let Masayo in.

Now there were problems with the phone connection, but eventually Masayo got a hold of the same guy and gave the phone number. He asked to speak to someone who “speaks Thai or Lao” so the cleaning woman got on the phone and listened, subsequently explaining to Masayo that he would call the hotel in thirty minutes.

Slowly but surely, she was getting somewhere. Through all this, I remained upstairs in bed, weak and feverish and oblivious to what was happening downstairs on my behalf. Forty-five minutes later, the guy from the Thai hospital called the hotel and wanted to talk directly to me. (The guesthouse could evidently receive international calls.) I couldn’t go downstairs very well, so the hotel guy came up to the room to assess my condition and report back to the hospital guy himself. Masayo lost her temper when the guy asked another million times if she really needed the ambulance to come, then finally said it would arrive in an hour.

Masayo’s helpful new friends.

Masayo had had dinner the night before at a nearby African restaurant and met several African guys, who she now ran into outside the hotel. She explained the situation and they offered to watch out for the ambulance for us. And finally it came.

Under my own power, I managed to get together my “important” day bag which never left my side – computer, passport, and insulin stuff, but no clothes or anything else – and stumble out of the hotel into the back of the ambulance. (Figuring I’d just get an IV for a few hours, I planned on being back at the guesthouse that night and so didn’t bother taking my big bag. Masayo thought this made no sense but wasn’t thinking perfectly straight either. She even prepaid for the room and left her own bags behind, climbing into the ambulance with me.)

At the border I lay in agony in the ambulance while someone took forever to process our passports. Our having just spent 90 days in Thailand must have raised some eyebrows, but they finally let us in.

Soon we were at the hospital; I threw up in the emergency room while a doctor said he suspected dengue fever. (Masayo had been told the same thing in the ambulance.)

Masayo was whisked away to pay the “entrance fee” for the hospital. She had no Thai money though, only Lao kip. They offered to drive her to an ATM, but the fee was more than you can withdraw in a single day. Eventually they said whatever she had would be enough for now, and they drove her to a bank – where the ATM didn’t work. At a second bank it did though; she paid and we were officially in the hospital.

By now I was in a room, hooked up to an IV and sleeping. A nurse told Masayo it would be several days: she knew she had to go back into Laos and get our bags. But she had no transportation to the border; she had given all her Thai cash to the hospital and maxed out the ATM for the day. And nobody accepted Lao money on this side of the border. Finally someone at the hospital offered to drive here; the authorities, amazingly, let her back out of Thailand and back into Laos, and she found a cheap bus back to Vientiane.

Masayo snapped this photo on one of her many trips across the border.

She checked out of the MOIC Guesthouse, grabbed both of our big bags, and finally had some food, a sandwich at a roadside stall. Then, clearer of mind and with me ensconced in my hospital room, she remembered that she had another ATM card for another bank account, and withdrew some Thai baht. Then she used her last few remaining kip to get back to the border.

The border guards, to my later amazement, let her cross the border for the third time that day. And her passport page tells the impressive story.

Finally, at 5:00 pm, she stumbled into my hospital room, dragging two heavy big bags with her and frazzled beyond recognition. I awoke from my stupor and, having been wondering what was going on all day, angrily asked, “What took you so long?!”

She has subsequently revealed that she could have murdered me right then and there. Hey what can I say – I was barely conscious.

Masayo in my hospital room.

Hospital life: on the quick mend

I stayed in the hospital for a couple of days, taking their medicine at regular intervals and eventually eating rice soup. Masayo slept on a couch in the room and spent days wandering the streets around the hospital, looking into vegetable markets and trying to make the time go faster.

At first, the hospital was also taking care of my diabetes but their decisions weren’t making sense to me. They’d check my BG; it’d be 350, and they’d give me six units of Humalog and give me rice soup. Clearly not enough insulin, for the meal or for my already-high BG. One day, annoyed by their inept diabetes care, I sent Masayo to 7-11 for cereal and milk and snuck off to the bathroom to shoot up for it.

Soon I was openly arguing with the staff about it until I yelled at the nurse one afternoon: “Look, I’m not here for diabetes, I’m here for dengue fever. You take care of that and I will decide about insulin from now on!” She sighed and gave up, agreeing, and even my blood sugars got (a little) better.

Showing off my IV.

I’m not convinced that the problem was actually dengue fever; the symptoms didn’t seem to indicate that. But whatever it was, the hospital fixed it in a few days. They also sold me some thyroid pills, which I trusted far more than the ones I’d purchased in the glass roadside case in Laos. Could taking those sunbaked pills have made me sick? Was there something in that staple that may have pierced the skin in my mouth? Was it really dengue fever?

I may never know.

When I was discharged they forgot to take the IV harness out of my wrist and I had to point it out; a nurse smirked and took care of it at her reception window. A curious mixture of medical competence and lackadaisical atmosphere.

The price for everything was about US$1,300; Masayo paid and I’ll have to owe it to her. I made myself feel better by calculating that if I’d been paying travel insurance lo these many months it would have been about the same price.

With Laos still beckoning but me still exhausted, we elected to stay in Nong Khai when I got out. We found a room at the Mut Mee Guesthouse, where we’d stopped a few days ago on the way into Laos to change money. We’ll spend a few days here while I fully recuperate and then continue the trip. Perhaps not back to Laos though, which is a shame: there must be so much else to see there.

But hey, how many people can say they rode over an international border as a patient in an ambulance? It’s an exclusive club!

And Masayo deserves special recognition for her amazing service in this story. What a trooper.

Thanks for reading. Suggested:

- Share:

- Read next: Day 201: Recuperating by the Mekong River: After the hospital

- News: Newsletter (posted for free on Patreon every week)

- Support: Patreon (watch extended, ad-free videos and get other perks)

Support independent travel content

You can support my work via Patreon. Get early links to new videos, shout-outs in my videos, and other perks for as little as $1/month.

Your support helps me make more videos and bring you travels from interesting and lesser-known places. Join us! See details, perks, and support tiers at patreon.com/t1dwanderer. Thanks!